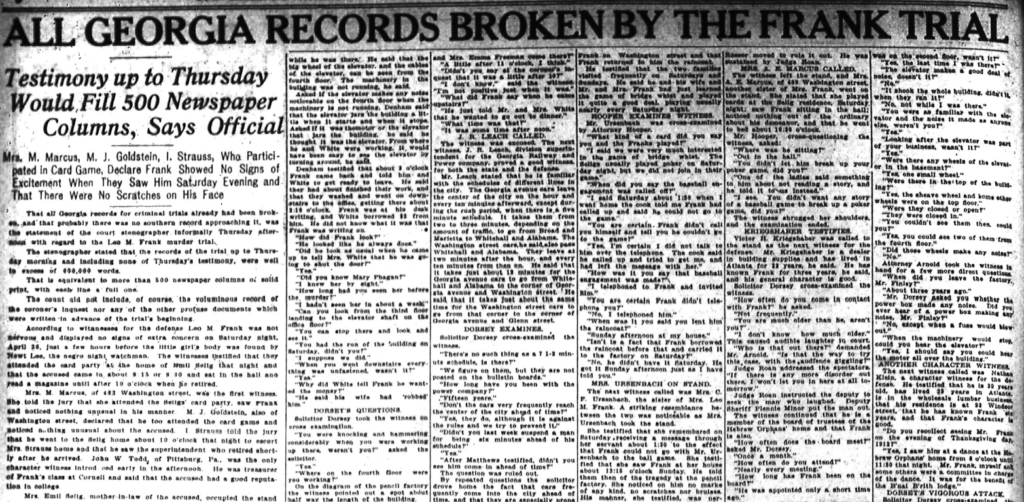

All Georgia Records Broken by the Frank Trial

Atlanta Journal

August 15th, 1913

Testimony up to Thursday Would Fill 500 Newspaper Columns, Says Official

Mrs. M. Marcus, M. J. Goldstein, I. Strauss, Who Participated in Card Game, Declare Frank Showed No Signs of Excitement When They Saw Him Saturday Evening and That There Were No Scratches on His Face

That all Georgia records for criminal trials already had been broken and that probably there was no southern record approaching it, was the statement of the court stenographer informally Thursday afternoon with regard to the Leo M. Frank murder trial.

The stenographer stated that the records of the trial up to Thursday morning and including none of Thursday’s testimony, were well in excess of 400,000 words.

That is equivalent to more than 500 newspaper columns of solid print, with each line a full one.

That court did not include, of course, the voluminous record of the coroner’s inquest nor any of the other profuse documents which were written in advance of the trial’s beginning.

According to witnesses for the defense Leo M. Frank was not nervous and displayed no signs of extra concern on Saturday night, April 26, just a few hours before the little girl’s body was found by Newt Lee, the negro night watchman. The witnesses testified that they attended the card party at the home of Emil Selig that night and that the accused came in about 8:15 or 8:30 and sat in the hall and read a magazine until after 10 o’clock when he retired.

Mrs. M. Marcus, of 482 Washington street, was the first witness. She told the jury that she attended the Seligs’ card party, saw Frank and noticed nothing unusual in his manner. M. J. Goldstein, also of Washington street, declared that he too attended the card game and noticed nothing unusual about the accused. I. Strauss told the jury that he went to the Selig home about 10 o’clock that night to escort Mrs. Strauss home and that he saw the superintendent who retired shortly after he arrived. John W. Todd, of Pittsburg, Pa., was the only character witness introduced early in the afternoon. He was treasurer of Frank’s class at Cornell and said that the accused had a good reputation in college.

Mrs. Emil Selig, mother-in-law of the accused, occupied the stand for a while and denied the allegations in the affidavit made by Minola McKnight, the cook for the Franks. She declared that the married life of her daughter had been a very happy one, but this testimony was ruled out by Judge Roan.

Harry Denham, assistant foreman at the factory, testified that Frank left the factory on Saturday, April 26, the day of the tragedy, shortly before 1 o’clock in the afternoon and returned at 3. Denham gave the names of different visitors to the factory during the period he was there and said that he and White left shortly after 3, leaving Frank in his office writing. He borrowed $2 from Frank as he went out.

The first witness of the afternoon session was Mrs. M. Marcus, of 483 Washington street. She was one of the members of the card party at the Selig residence on the night of Memorial day. She testified that the group of friends with whom she was, played cards every Saturday night at the houses of different members. She testified that she saw Frank in the Selig residence between 5:30 and 8:45 o’clock; that he sat in the hall most of the time reading a magazine, and that he went up to bed about 10 or 10:30 o’clock. Nothing was brought out on examination.

Harry Denham was called as the next witness, but did not answer.

M. J. Goldstein, of 236 Washington street, was called as the second witness.

Mr. Goldstein testified that he was a member of the card party in the Selig home on the night of April 26. He said that he arrived there about 8:15 o’clock, and Mrs. Selig, Mrs. Leo M. Frank and Mrs. Marcus were already there. He said he played cards in the dining room; that Frank was seated in the hall.

In answer to a question by Attorney Arnold, he said there was absolutely nothing unusual about Frank that night. To the best of his recollection, said the witness, Frank went to bed about 10:30 o’clock, and his wife went fifteen minutes later. There were no scratches or bruises visible upon Frank, said he.

Attorney Hooper cross-examined the witness briefly, developing nothing material.

Miss Eula Mae Flowers was called as the next witness. She did not respond and I. Strauss was called.

Mr. Strauss testified that he called at the Selig home about 10 o’clock on the night of April 26, to get his wife and escort her home. He stopped about an hour, he said, and played cards a while. From where he sat at the card table, he said, he could see Frank seated in the hall, and noticed nothing unusual about him. Frank went to bed soon after he, the witness, got there, and Mrs. Frank went soon afterward.

Attorney Hooper cross-examined the witness, asking a few questions, concluding with, “How long did you play?” “An hour, maybe a little less,” answered the witness. “How did you come out?” “I can’t remember.”

MRS. SELIG ON STAND.

Mrs. Emil Selig was recalled as the next witness. Attorney Arnold asked the solicitor for copies of the affidavit that Minola McKnight made, remarking that he wanted to question Mrs. Selig about them. The solicitor gave them to him.

Mr. Arnold asked specifically about every detail of every statement in the affidavit, and Mrs. Selig denied each. Mr. Arnold brought out from Mrs. Selig that “Mrs. Rausin,” referred to in the affidavit, probably was Mrs. Ursenbach, her daughter.

Solicitor Dorsey cross-examined the witness.

“How long after Frank’s arrest did Mrs. Frank go to see him?”

“That week, I think.”

Later on in his examination, Mr. Dorsey reverted continually to Mrs. Frank’s first visit to her husband in the jail. Mrs. Selig said that not only did she not remember when that first visit was, but that also she would make no effort to remember it. Asking the solicitor what he was trying to imply by his question, the witness admitted that Mrs. Frank was at home Thursday and Wednesday and that she spent some time each day reading on the front porch.

Mr. Dorsey asked if Mrs. Frank went to see her husband before May 3, and the witness answered that she did not know. He asked if Frank had not been a prisoner two weeks when Mrs. Frank called, and the witness said she did not think so.

Mr. Arnold asked Mrs. Selig, when the cross-examination was concluded, “Was the married life of Mr. and Mrs. Frank happy?”

“Exceptionally happy,” answered the witness.

The solicitor objected to the question and answer and asked that they be ruled out. Before Judge Roan ruled, Mr. Rosser objected to all questions and answers by the solicitor about Mrs. Frank’s delay in calling upon her husband at the jail. Arguing his motion, Mr. Rosser declared that in this case it seemed that the court had forgotten the rules of circumstantial evidence and seemed to think that any circumstance was relevant, whereas, as a matter of fact, only circumstances pointing to the guilt or innocence of the accused were irrelevant.

“Suppose I had a veritable virago for a wife,” said Mr. Rosser, “and when I was locked up she didn’t come near me. Or suppose I had a very loving wife whom my inherent decency made me ask to stay away from the jail. How could that show whether I was guilty or innocent?”

Judge Roan ruled out all questions relating to the actions of Mrs. Frank, and also ruled out Mr. Arnold’s question as to the happiness of their married life.

Mrs. Selig was cross-examined at length by Mr. Dorsey. She was asked especially regarding any statement which she might have made to Minola McKnight, the cook, at the time when Minola was carried downtown by officers.

The witness did not remember anything, but denied every question which pointed toward the affidavit of the negress as being in any way correct.

She did not remember what time Frank left home on the morning of April 26. The witness said that on that day she did not see Albert McKnight at the house, in the morning or at dinner time or at night. She had seen Minola talking to Albert not more than two or three times, she said.

EMPHATIC DENIALS.

The solicitor questioned Mrs. Selig closely about the different statements in the affidavit by the cook, but got nothing from her except emphatic denials. The witness said that she was not up and did not remember seeing any officers who came to the residence for Frank on Sunday morning.

The solicitor asked a number of questions about the pay of Minola McKnight, which Mrs. Selig said is $3.50 a week and has been that since the negress first was employed. Mrs. Selig said that one week she did advance Minola $3 of her next week’s wages, and took the amount out the following week.

Mrs. Selig said that one week she did give Minola $5 with instructions to bring back the change, and that the cook brought back only $1 and that the following week she deducted 50 cents. The solicitor asked if Mrs. Frank had not given to Minola a hat since the tragedy. Mrs. Selig said her daughter had given Minola a hat, but she did not remember whether it was before or after the tragedy.

PITTSBURG WITNESS.

John W. Todd was called as the next witness. He is a citizen of Pittsburg, Pa., and assistant purchasing agent of the Crucible Steel company. He testified that he attended Cornell university at the same time Frank was there, and knew him as a fellow-student for four years. He testified that he, the witness, was treasurer of his class. He said that Frank’s general character was very good.

Harry Denham, assistant foreman on the fourth floor of the National Pencil factory, was called. He testified that he was paid off Friday afternoon and went back to the factory Saturday morning about 7:30 o’clock to work on some machinery on the fourth floor.

He said that Holloway was there when he arrived, but that he didn’t know whether Frank was in the building at that time.

He said that Mae Barrett came up about 11:15 o’clock, to the best of his recollection, and stayed there about three-quarters of an hour. She came, said he, for a crocus sack, and stood around and talked awhile.

He testified that Mrs. Emma Freeman and Miss Corinthia Hall came up and stayed about fifteen minutes. He said they got something and wrapped it up. He thought it was a coat.

He said that the next person who came to the fourth floor was the wife of Arthur White, who also was on the fourth floor at work. It was about 12:30 when Mrs. White came. Mrs. White and her husband had a long talk.

The next person who came up was Frank, who told them he was going to dinner and would like to close the doors, and asked Mrs. White if she would leave. He supposed it was about five minutes to 1 when Frank came up. Frank stayed only a moment, and Mrs. White went out right behind him.

Attorney Arnold questioned the witness closely as to whether he heard the elevator running about that time. He testified that he did not hear it running about that time or at all during the day while he was there. He said that the big wheel of the elevator, and the cables of the elevator, can be seen from the fourth floor. The machinery in the building was not running, he said.

Asked if the elevator makes any noise noticeable on the fourth floor when the machinery is not running, Denham said that the elevator jars the building a little when it starts and when it stops. Asked if it was the motor or the elevator that jars the building, he said he thought it was the elevator. From where he and White were working, it would have been easy to see the elevator by turning around, he said.

Denham testified that about 2 o’clock Frank came back and told him and White to get ready to leave. He said they had about finished their work, and that they washed and went on downstairs to the office, getting there about 3:19 o’clock. Frank was at his desk writing, and White borrowed $2 from him. He did not know what it was that Frank was writing on.

“How did Frank look?”

“He looked like he always does.”

“Did he look as usual when he came up to tell Mrs. White that he was going to shut the door?”

“Yes.”

“Did you know Mary Phagan?”

“I knew her by sight.”

“How long had you seen her before the murder?”

“I hadn’t seen her in about a week.”

“Can you look from the third floor landing to the elevator shaft on the office floor?”

“You can stop there and look and see it.”

“You had the run of the building on Saturday, didn’t you?”

“I suppose we did.”

“When you went downstairs everything was unfastened, wasn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Why did White tell Frank he wanted the money?”

“He said his wife had ‘robbed’ him.”

DORSEY’S QUESTIONS.

Solicitor Dorsey took the witness on cross-examination.

“You were knocking and hammering considerably when you were working up there, weren’t you?” asked the solicitor.

“Yes.”

“Where on the fourth floor were you working?”

On the diagram of the pencil factory the witness pointed out a spot about half way the length of the building.

“You were working over the back of the office floor, then, weren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“How far were you from the stairway?”

“Forty feet.”

At the instance of Solicitor Dorsey, he designated the distance in the court room.

“You couldn’t have seen the elevator from where you were, because it opens to the side, doesn’t it?”

“I couldn’t have seen it but I could have seen the wheels moving.”

“But you were too busy with your work to look at it, weren’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“What kind of doors are on the elevator?”

“They are sliding doors; you can slide them up and down.”

“They are always down when the factory is not running, aren’t they?”

“Sometimes they’re not.”

“Did you notice whether the door was up or down, the day you worked there?”

“Do you know whether the box to the switch of the motor on the second floor is kept locked?”

“I don’t know.”

FRANK CAME AT 1 O’CLOCK.

“When was the first time Frank came up to where you were working?”

“About 10 minutes to 1 o’clock.”

“Didn’t he come up earlier than that?”

“No.”

Solicitor Dorsey read a portion of Denham’s evidence before the coroner’s jury, wherein Denham said that Frank came up there about 12 o’clock.

“Is that right?” asked the solicitor.

“I’m not certain,” replied the witness.

“Are you certain now about the time?”

“No, sir.”

“How close did Frank come to where you were working, when he came up?”

“Within about 10 feet of us.”

“What’s the time he talked to Mrs. White, is it?”

“How many times did Frank come up that day?”

“Twice.”

“Were you through when he returned at 3 o’clock?”

“Yes, we were washing when he came back upstairs that time.”

“What time was that?”

RETURNED AT 3 O’CLOCK.

“Three o’clock.”

“You told the coroner that it was about 10 or 15 minutes to 3, didn’t you?”

“I’m not certain.”

“Frank said he was going right out, didn’t he, when he was up there the first time?”

“No, he said he wanted to.”

“Do you know whether he went out or not?”

“No.”

“On April 28 you went to the office floor, didn’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You saw some blood in the metal room near the girls’ dressing room, didn’t you?”

“No, sir.”

“Didn’t you say at the coroner’s jury you saw this blood?”

“I said I saw something that I thought was blood.”

“Did you hear the wind blowing Saturday?”

“Yes, I heard it snapping the blinds.”

“Did you hear any unusual noise in the building?”

“No, sir.”

“There is a door at the head of the stairs, as you come up to the floor you were working on, isn’t there?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Is there a way to lock or fasten it?”

“No, sir.”

“Isn’t there a way to tie it?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Could a man on the office floor hear anybody walking up the aisle from the back of the fourth floor?”

“No, sir. I don’t think so.”

Denham then described how on April 26 he went down to the second floor to get some boards cut. He went to the band saw, he said, and that the boards were necessary for the work they were doing on the fourth floor.

“Didn’t you say at the coroner’s inquest that you did not leave the fourth floor between 7 and 3 o’clock?”

“I think I told them that.”

“That is a mistake then, is it?”

“Yes, it was a mistake.”

In answer to another question, Denham said that he and White had hunted up Holloway to get him to cut the boards for them.

“A person could have come into Frank’s office and you wouldn’t know anything about it, would you?”

“Yes, anybody could have come in or gone out.”

“You said at the coroner’s inquest that when Frank came upstairs, you did not see whether his face was flushed or not?”

“Yes. I didn’t pay any attention to him then.”

“What time did Miss Corinthia Hall and Mrs. Emma Freeman come there?”

“A little after 11 o’clock, I think.”

“Didn’t you say at the coroner’s inquest that it was a little after 10?”

“I don’t know,” said the witness.

“I’m not positive just when it was.”

“What did Frank say when he came upstairs?”

“He just told Mr. and Mrs. White that he wanted to go out to dinner.”

“What time was that?”

“It was some time after noon.”

J. R. LEACH CALLED.

The witness was excused. The next witness, J. R. Leach, division superintendent for the Georgia Railway and Power company, proved a good witness, for both the state and the defense.

Mr. Leach stated that he is familiar with the schedules of different lines in the city. The Georgia avenue cars leave the center of the city on the hour and every ten minutes afterward, except during the rush period, when there is a five minute schedule. It takes them from two to three minutes, depending on the amount of traffic, to go from Broad and Marietta to Whitehall and Alabama. The Washington street cars, he said, also pass Whitehall and Alabama. They leave at two minutes after the hour, and every ten minutes from then on. He said that it takes just about 12 minutes for the Georgia avenue cars to go from Whitehall and Alabama to the corner of Georgia avenue and Washington street. He said, that it takes just about the same time for the Washington street cars to go from that corner to the corner of Georgia avenue and Glenn street.

DORSEY EXAMINES.

Solicitor Dorsey cross-examined the witness.

“There’s no such thing as a 7 1-2 minute schedule, is there?”

“We figure on them, but they are not posted on the bulletin boards.”

“How long have you been with the power company?”

“Fifteen years.”

“Don’t the cars very frequently reach the center of the city ahead of time?”

“Yes, they do, although it is against the rules and we try to prevent it.”

“Didn’t you last week suspend a man for being six minutes ahead of his schedule?”

“Yes.”

“After Matthews testified, didn’t you see him come in ahead of time?”

The question was ruled out.

By repeated questions the solicitor drove home the fact that cars frequently come into the city ahead of time, and that they are especially prone to come in ahead when crews are about to be relieved.

Mr. Arnold, on re-direct examination, brought out the statement that the English avenue car has a pretty hard schedule.

C. D. ALBERT TESTIFIES.

The next witness to take the stand was Prof. C. D. Albert. He is head of the department of machine designing at Cornell university. His home is in Ithaca, N. Y., and he has had his position on the Cornell faculty for five years. He stated that he knew Leo M. Frank from October, 1904, to June, 1908. He was then an instructor in the mechanical laboratory, and Frank was student under him. He knew Frank very well and his character was good. The witness was not cross-examined. When he left the stand he went over and shook hands with Frank, who greeted him very cordially, Prof. Albert sitting down and talking with Frank and the prisoner’s wife.

J. E. Vanderholt, of Ithaca, N. Y., was called. He is the foreman in the Cornell university foundry. He testified that he had known Frank since 1903 and had been associated with him for two years at Cornell university. He testified that he knew Frank’s character to be good. Attorney Hooper, cross-examining him, asked “How long have you been at Cornell?”

“Twenty-five years,” said the witness.

“How many students on an average are there in that university each year?”

“Two hundred to three hundred in my department.”

“How many are there in the school?”

“About 1,200 this year.”

“Well, you didn’t take any special note of Leo M. Frank, did you?”

“I came in contact with him every alternate day.”

“You don’t mean to say that you know all about the morals of all these 300 men that you teach every year, do you?”

“Well, I see them all.”

“You are never out with them when they start to paint the town red, are you?”

“No, sir.”

“Some of them do paint the town red, don’t they?”

“A certain class of them do.”

“You don’t pretend to tell about the morals of Frank outside of your class, do you?”

“I do not.”

MAE FLOWERS ON STAND.

The witness was excused, and Miss Eula Mae Flowers was called.

“Did you work in the pencil factory on Saturday, April 26?” Mr. Arnold asked Miss Flowers.

“No, sir.”

“Did you work Friday, the day before?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did Herbert Schiff get the data from you for the financial sheet, Friday?”

“Yes, he got it Friday night.”

“What time did he get it?”

“At 10 minutes to 6 o’clock.”

Miss Flowers continued that the data which Schiff got showed the production in her department for the preceding weeks. Attorney Hooper cross-examined the witness.

“Did you always turn these slips in Friday night?”

“Yes.”

“Did it touch Friday’s production?”

“No, sir.”

“What particular department is yours?”

“The packing department.”

“Did you see blood spots on the floor in the metal room after the killing?”

“No, sir.”

“How did it happen that you didn’t see them?”

“Well, it was not my business.”

“And you had no curiosity to see them?”

“No, sir.”

Witness was excused.

SATURDAY BALL GAME.

C. F. Ursenbach, of 62 Washington street, whose wife is a sister of Mrs. Leo M. Frank, was the next witness. He testified that on Friday, April 25, he called Frank over the telephone and asked him if he would go to the game on Saturday afternoon.

The witness said that Frank replied he did not know for certain then but would call him later and let him know. He said that when he went home Saturday about 1:30, his cook told him Frank had called up and said he could not go to the game.

He said that Frank was at his house twice on Sunday, the first time about 12:15, when he told him and Mrs. Ursenbach of the tragedy at the factory. He noticed no scratches or bruises on Frank. He said that Frank seemed disturbed and nervous as a man would be naturally under the circumstances.

The witness said he himself felt disturbed. He testified that Frank came to the house again in the afternoon and that when Frank left about 4:30 o’clock he borrowed the witness’ rain coat. That same evening, Sunday, he and Mrs. Ursenbach met Mr. and Mrs. Frank on Washington street and that Frank returned to him the raincoat.

He testified that the two families visited frequently on Saturdays and Sundays. He said he and his wife and Mr. and Mrs. Frank had just learned the game of bridge whist and played it quite a good deal, playing usually nearly every Saturday night.

HOOPER EXAMINES WITNESS.

Mr. Ursenbach was cross-examined by Attorney Hooper.

“What kind of a card did you say you and the Franks played?”

“I said we were very much interested in the game of bridge whist. The Seligs usually played poker on Saturday night, but we did not join in their game.”

“When did you say the baseball engagement was called off?”

“I said Saturday about 1:30 when I went home the cook told me Frank had called up and said he could not go to the game.”

“You are certain Frank didn’t call you himself and tell you he couldn’t go to the game?”

“Yes, I’m certain I did not talk to him over the telephone. The cook said he called up and tried to get me, and had left the message with her.”

“How was it you say that baseball engagement was made?”

“I telephoned to Frank and invited him.”

“You are certain Frank didn’t telephone you?”

“No, I telephoned him.”

“When was it you said you lent him the raincoat?”

“Sunday afternoon at my house.”

“Isn’t it a fact that Frank borrowed the raincoat before that and carried it to the factory on Saturday?”

“No, he didn’t have it Saturday. He got it Sunday afternoon just as I have told you.”

MRS. URSENBACH ON STAND.

The next witness called was Mrs. C. F. Ursenbach, the sister of Mrs. Leo M. Frank. A striking resemblance between the two was noticeable as Mrs. Ursenbach took the stand.

She testified that she remembered on Saturday, receiving a message through her servant about 1:30 to the effect that Frank could not go with Mr. Ursenbach to the ball game. She testified that she saw Frank at her house about 12:15 o’clock Sunday. He told them then of the tragedy at the pencil factory. She noticed on him no marks of any kind, no scratches nor bruises. His manner, she testified, was nervous as a man naturally would be under the circumstances. She said that he returned to the house Sunday afternoon and she and her husband met Mr. Frank and his wife on Washington street Sunday evening.

Attorney Arnold borrowed from the solicitor the Minola McKnight affidavit and read to Mrs. Ursenbach that portion which claimed to report remarks which passed between Mrs. Ursenbach and Mrs. Frank. In the affidavit Mrs. Ursenbach was referred to as “Miss Rausin.” Mrs. Ursenbach explained that her given name is Rosalind. She supposed “Miss Rausin” was the negro’s pronunciation of her name. Reading the affidavit, Mr. Arnold asked the witness if she had said to Mrs. Frank: “It’s mighty bad,” and if Mrs. Frank replied: “Yes. I’m going to get after her.”

Mrs. Ursenbach stated that nothing of the kind had occurred.

Mrs. Ursenbach was cross-examined by Attorney Hooper. The witness stated that she remembered her husband lending the rain coat to Frank Sunday afternoon.

“Where was the rain coat Saturday?”

“In my house.”

“What time Saturday did you notice it?”

“I don’t know that I noticed it that day?”

“Then you don’t know that it was in your house?”

“No, but I know it was there Sunday when my husband asked Mr. Frank if he wouldn’t wear it.”

“Who suggested speaking to Minola McKnight about the case?”

“Why, I don’t know. I didn’t speak to her, and I didn’t hear anybody else.”

“What did Frank tell you about the crime?”

“He told me how he was called down there, and how horrible it was.”

“What time was it he told you that?”

“A little after 12.”

“What else did he say about it?”

“He was talking to Mr. Ursenbach and I was frequently out of the room.”

“Tell us something that he said.”

SAID CRIME WAS BRUTAL.

“He said it was a brutal crime.”

“Didn’t he say anything about getting a lawyer or hiring the Pinkertons?”

“I didn’t hear him.”

“What time did he say he left the factory?”

“He didn’t say, I think.”

“How did he show his nervousness?”

“He kept patting his foot on the floor.”

“Did he wring his hands or run them through his hair?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Did he say how he slept that night?”

“He didn’t say.”

“What did he tell you about the ringing of the telephone?”

“He said he thought he heard it in his sleep.”

“What else did he say about the crime?”

“He said they were trying to find out who killed the girl.”

“Did he tell you about identifying the body?”

“Yes. He said he was down there in the afternoon.”

“Are you sure he said afternoon?”

“I think so.”

“Did he say he saw the body?”

He said the body was a gruesome sight.”

“Did he mention the changes he made in the time clock?”

“I didn’t hear anything like that.”

“Did he say he suspected Gantt, or Newt Lee, or anybody?”

DISTRUSTED GANTT.

“He said he was sorry he left Gantt into the factory because he distrusted him.”

“He didn’t say that he thought Newt Lee or Gantt did it?”

“No, I don’t remember that he mentioned Lee. I was in and out of the room. Oh, yes, he did say that Newt Lee was a good negro as far as he knew.”

Witness said he did not know when she heard the name of the murdered girl. She said she was at the Selig home again Monday evening.

“What did Mr. Frank say then?”

“He said the detectives seemed to suspect him.”

“Was he nervous then?”

“I don’t think so.”

“You mean to say Frank was nervous before he was suspected, and not nervous after he was suspected?”

“Well, really I don’t remember. I think he patted his foot that afternoon.”

“When was the last time you played bridge with him before the tragedy?”

“It was that week. I don’t remember the day.”

“When did you play after the murder?”

“We didn’t play, but Sunday night Mr. Frank phoned to Mr. Ursenbach to see if we were going to.”

“Did you hear the conversation?”

The witness said no, and Attorney Rosser moved to rule it out. He was sustained by Judge Roan.

MRS. A. E. MARCUS CALLED.

The witness left the stand, and Mrs. A. E. Marcus, of 489 Washington street, another sister of Mrs. Frank, went on the stand. She stated that she played cards at the Selig residence, Saturday night; saw Frank sitting in the hall; noticed nothing out of the ordinary about his demeanor, and that he went to bed about 10:30 o’clock.

Mr. Hooper, cross-questioning the witness, asked:

“Where was he sitting?”

“Out in the hall.”

“You didn’t let him break up your poker game, did you?”

“One of the ladies said something to him about not reading a story, and he told it to us instead.”

“I see. You didn’t want any story of a baseball game to break up a poker game, did you?”

The witness shrugged her shoulders, and the examination ended.

KRIEGSHABER TESTIFIES.

Victor H. Kriegshaber was called to the stand as the next witness for the defense. Mr. Kriegshaber is a dealer in building supplies and has lived in Atlanta for 22 years, he said. He has known Frank for three years, he said, and his general character is good.

Solicitor Dorsey cross-examined the witness.

“How often do you come in contact with Frank?” he asked.

“Not frequently.”

“You are much older than he, aren’t you?”

“I don’t know how much older.” This caused audible laughter in court.

“Who is that out there?” demanded Mr. Arnold. “Is that the way to try this case, with the audience giggling?”

Judge Roan addressed the spectators. “If there is any more disorder out there, I won’t let you in here at all tomorrow.”

Judge Roan instructed the deputy to seek the man who laughed. Deputy Sheriff Plennie Minor put the man out.

The witness continued that he is a member of the board of trustees of the Hebrew Orphans’ home and that Frank is also.

“How often does the board meet?” asked Mr. Dorsey.

“Once a month.”

“How often do you attend?”

“Nearly every meeting.”

“How long has Frank been on the board?”

“He was appointed only a short time ago.”

“How many times, then, have you seen him at these meetings? Give us an estimate.”

“About twice.”

The witness said that he had seen Frank at the Orphans’ home with Frank’s uncle several times. He did not know Frank socially, said the witness, but had met him a few times at various places.

MAX GOLDSTEIN.

Max Goldstein, a lawyer, was called to the stand. He testified that he has known Frank for three years and a half and that his general character is good. He said that for a year he lived on the same street with Frank and saw him nearly every day then. Also he met Frank in B’nai B’rith work, he said.

“Are you married?” asked Solicitor Dorsey, cross-examining the witness.

“No, sir.”

“You don’t associated a whole lot, socially, then, with Frank, do you?”

“No, sir.”

The witness testified that he met Frank at the Progress club occasionally, too.

Sidney Levy was called as the next witness. He is a clerk for the Atlanta Joint Terminals company.

Levy Testified that Frank’s reputation is good, and was excused.

RABBI MARX TESTIFIES.

Rabbi David Marx was called to the stand. He testified that he has lived in Atlanta eighteen years; that he knows Frank very intimately, and that Frank’s character is exceptionally good. He was excused.

D. I. McIntyre, a member of the firm of Haas & McIntyre, insurance agents, was the next witness. He said that he has known Frank for some time and that Frank’s general character is good.

Solicitor Dorsey addressed the court. “We would like to have the privilege of calling this witness back later for further questioning, your honor,” said he. Attorney Arnold said, “We don’t want to hold him. He’s a business man.”

“We will subpoena him again,” said the solicitor.

“I intend to leave for New York tomorrow night,” said Mr. McIntyre.

Solicitor Dorsey said, “All right.”

Dr. B. Wildauer, a dentist, of 69 Windsor street, was the next witness called. He said that he had lived in Atlanta since 1890; that he had known Frank five years and that his general character is good.

Solicitor Dorsey cross-questioned him briefly.

“You never knew about his conduct in the pencil factory with the girls, did you?”

“I did not.”

“You didn’t know what occurred at the pencil factory on Saturdays, holidays and nights, did you?”

“I did not.”

JOHN FINLEY.

John Finley, of 16 Irene avenue, formerly assistant superintendent of the pencil factory, was called next. He testified that he had known Frank for five years, and that his character was good. The solicitor cross-questioned the witness at considerable length, digging into other matters than Frank’s character. The solicitor developed that Finley had gone to the pencil factory as master mechanic, and later was made assistant superintendent.

“What is your business now?”

“I’m superintendent for Dittler Brothers.”

“Are you any relative of Frank or his wife?”

“Not that I know of.”

“When did you leave the employ of the pencil factory?”

“About three years ago.”

“How have you kept in touch with Frank since that time?”

“I haven’t.”

“Do you know what his actions at the pencil factory have been since you left?”

“I do not.”

“Did you know about that old cot down there in the basement?”

“I did not.”

The witness testified that at the time he worked there Frank usually left on Saturday about 1 o’clock. He said that at that time they did not have a nightwatchman, although a Mr. Green acted as day watchman.

“Do you know about the elevator there?” asked the solicitor.

“Yes, sir, I had it put in.”

“Where is the switch box on the second floor?”

“It’s on the left hand side of the elevator shaft, when a person faces the elevator.”

“Did you keep it closed or open when you were there?”

“We kept it closed when I was there.”

“Where did you keep the key?”

“I usually kept one in my pocket, and there was a key box for another in the office.”

The witness explained that it was the custom after anybody had used the elevator, to lock the box and put the key in the office.

“All the machinery of the elevator was on the second floor, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, the last time I was there?”

“The elevator makes a good deal of noise, doesn’t it?”

“No.”

“It shook the whole building, didn’t it, when they run it?”

“No, not while I was there.”

“You were as familiar with the elevator and the noise it made as anyone else, weren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Looking after the elevator was part of your business, wasn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Were there any wheels of the elevator in the basement?”

“Yes, one small wheel.”

“Were there in the top of the building?”

“Yes, the sheave wheel and some other wheels were on the top floor.”

“Were they closed or open?”

“They were closed in.”

“You couldn’t see them then, could you?”

“Yes, you could see two of them from the fourth floor.”

“Did those wheels make any noise?”

“No.”

Attorney Arnold took the witness in hand for a few more direct questions.

“When did you leave the factory, Mr. Finley?”

“About three years ago.”

“Mr. Dorsey asked you whether the power box made any noise. Did you ever hear of a power box making any noise, Mr. Finley?”

“No, except when a fuse would blow out.”

“When the machinery would stop, could you hear the elevator?’

“Yes, I should say you could hear the motor all over the building.”

ANOTHER CHARACTER WITNESS.

The next witness called was Nathan Klein, a character witness for the defense. He testified that he is 30 years old, has lived 29 years in Atlanta, is in the wholesale lumber business, that his residence is at 93 Windsor street, that he has known Frank six years, and that Frank’s character is good.

“Do you recollect seeing Mr. Frank on the evening of Thanksgiving day, 1912?”

“Yes, I saw him at a dance at the Hebrew Orphans’ home from 8 o’clock until 11:30 that night. Mr. Frank, myself and some others were committee in charge of the dance. It was for the benefit of the B’nai B’rith lodge.”

DORSEY’S VIGOROUS ATTACK.

Solicitor Dorsey cross-examined the witness, and injected new life into the sluggish proceedings by going after the witness in probably the most vigorous fashion of any whom he had attacked during the day.

“You’ve been with Mr. Frank a good deal down at the jail, haven’t you?”

“Yes.”

“How much.”

“From thirty minutes to an hour five days during the week.”

“Were you there when Conley sought an interview with Frank?”

Attorney Rosser objected to the words, “sought an interview” on the ground that they implied a conclusion, and Judge Roan sustained him.

“Were you there when Conley asked to confront Frank?”

Attorney Rosser entered a vigorous objection. He was sustained by the court.

“Then tell us just what did happen, Mr. Klein. Did Conley come down there?”

“Yes, he was brought there by Detective Black, Scott and Campbell.”

“Did Frank see him?”

“No.”

“Did you send down a message to them?”

REFUSED TO SEE CONLEY.

“Yes, I told them that Mr. Frank would see no one.”

“Did they bring Conley to the front of Frank’s cell?”

“Yes, they brought the negro to the front of his cell.”

“Did Frank come out and see Conley?”

“No, I went to the front and acted as spokesman.”

“Then Frank didn’t come out at all, did he? He stayed in the back end of the cell all the time?”

“I said he did not come out.”

“He wouldn’t see the detectives, either, would he?”

“No.”

“He wouldn’t even see his own detective, Scott, would he?”

Attorney Rosser objected to Solicitor Dorsey referring to Scott as Frank’s own detective.

“All right, then,” said the solicitor. “We’ll call him Detective Scott. Frank didn’t see him, did he?”

“No, he didn’t see him.”

“What did Frank say?”

“He said he would see nobody except in the presence of his attorney.”

“Did Frank offer to send for his attorney then?”

“He said if they wanted to see him they’d have to go and get Mr. Rosser.”

“Was this before or after Conley had been taken to the factory?”

“I think it was the day he admitted writing the notes on Friday.”

“What was Frank’s manner at that time?”

“He was perfectly cool. He considered Conley the same as one of the city detectives.”

“How do you know that?”

“I conferred with him and he said so.”

“Why did he say that he wouldn’t see Scott?”

“He said he would see none of the city detectives, and that included Scott?”

“No.”

“Then you just concluded that. Now tell us how Frank looked when Conley came up that day.”

“He looked very much disappointed, because the grand jury had just indicted him. He expected to be cleared before the grand jury.”

“Why did he say he expected to be cleared?”

“He didn’t say why. I just know that he expected to be cleared.”

“What did he do when the news came that he had been indicted?”

“I went there with Dr. Wildauer, and Frank and he didn’t think it was possible. He said he had been in a hopeful frame of mind.”

“When did you first see him after he was arrested?’

“I saw him at the station house.”

“He wasn’t arrested then, was he?”

“The papers said he was being detained, but there was a policeman on guard over him.”

“He expected to go to jail, didn’t he?”

“I don’t know whether he did or not.”

“Did you see the telegrams he sent to his uncle?”

“No.”

“Who was his uncle?”

“Mr. Moses Frank.”

“How often did you go to the National Pencil factory to see Mr. Frank?”

MANY VISITED HIM.

“I should say fifteen times or more, in connection with B’nai B’rith work.”

“Who else besides yourself was with Mr. Frank at the jail?”

“Several friends went down to see him. Sometimes there’d be as many as six or seven there at once.”

“Were you one of those who helped to make arrangements to shift the […]

END OF TRIAL OF LEO M. FRANK IS NOW IN SIGHT

[…] watch so that there would be somebody on guard there with him all the time?”

“I don’t know as to being on guard there with him. I know I went to see him nearly every day, and that Dr. Wildauer went to see him I think nearly every day, and that many other friends went to see him.”

This concluded the cross-examination. Before the witness was excused Attorney Rosser asked, “Do you remember whether I was in the city on the day they took Conley to the jail to see Frank, or whether I was in north Georgia trying a case?”

“I don’t know as to that.”

R. B. SONN CALLED.

R. B. Sonn, of 478 Washington street, superintendent of the Hebrew Orphans’ home, resident of Atlanta for the past 25 years, was the next witness. He testified to Frank’s good character.

Alex Dittler, of 340 Courtland street, a resident of Atlanta for 33 years, present secretary of the Jewish Educational Alliance and the Federation of Jewish Charities, formerly a deputy city marshal, and for a number of years a deputy clerk of the superior court in this county, also testified as to the good character of the accused.

Arthur Heyman, a law partner of Solicitor Dorsey, was another character witness. He said that he had known the defendant for three or four years and that his general reputation is good.

The solicitor cross-examined his partner, and brought out the statement that Mr. Heyman had seen Frank only seven or eight times and talked to him alone for no more than a few minutes at a time. Mr. Heyman admitted that he knew nothing of Frank’s relations with girls at the factory nor of how he spent his afternoons and holidays.

COURT ADJOURNS.

Court then adjourned until 9 o’clock Friday morning.

Luther Z. Rosser, chief counsel for the defense stated privately to reporters that he hoped to conclude the defense cause by Friday night.