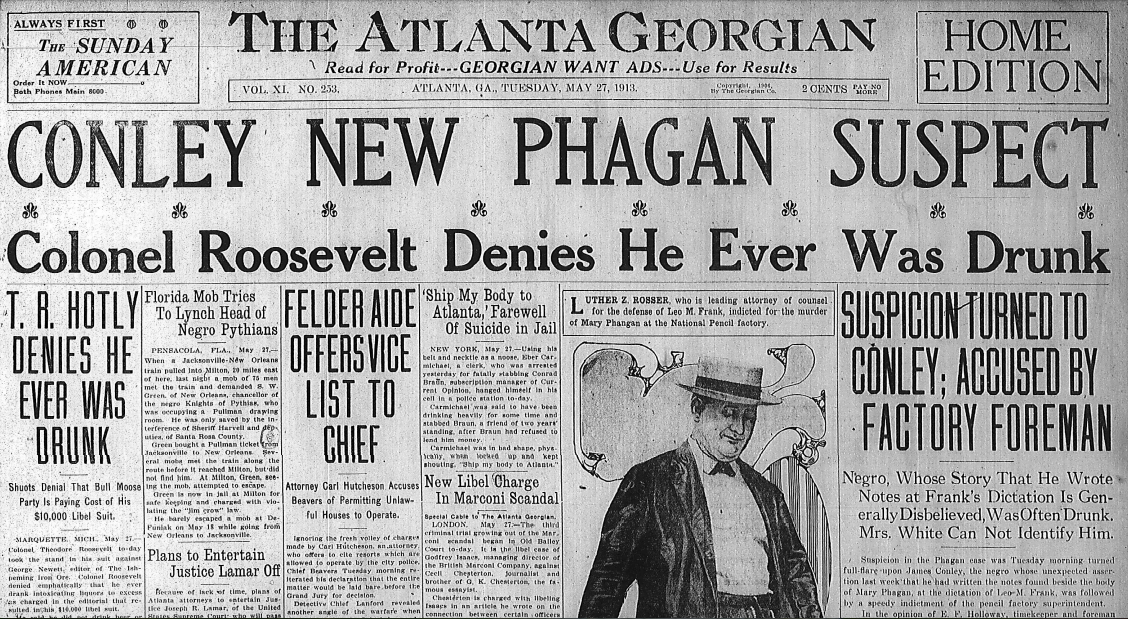

Suspicion Turned to Conley; Accused by Factory Foreman

Atlanta Georgian

Tuesday, May 27th, 1913

Negro, Whose Story That He Wrote Notes at Frank’s Dictation Is Generally Disbelieved, Was Often Drunk. Mrs. White Can Not Identify Him.

Suspicion in the Phagan case was Tuesday morning turned full-flare upon James Conley, the negro whose unexpected assertion last week that he had written the notes found beside the body of Mary Phagan, at the dictation of Leo M. Frank, was followed by a speedy indictment of the pencil factory superintendent.

In the opinion of E. F. Holloway, timekeeper and foreman in the factory, Conley is the guilty man.

Careful study of the negro’s story has revealed many absurdities in its structure, wherein evidences of childish cunning are rife in an effort to throw the blame onto Frank. It is this which has served to bring the deed to Conley’s door.

However, Mrs. Arthur White, wife of a machinist at the factory, who testified that she saw a negro lurking in the building between 12 noon and 2 o’clock on the afternoon of the murder, denied the published report in an afternoon paper that she had identified Conley as the one. Mrs. White stated Tuesday morning that she had secured only a glimpse of the man. It may have been Conley, or another negro. Mrs. White was asked to pick Conley out of a crowd of twelve negroes some time ago, but her identification was a second choice.

The police, in spite of bending every effort to show that Frank is guilty, therefore, have resorted to a dissection of Conley’s story. One of its weakest links, they believe, is the negro’s quotation of Frank’s statement to him, “Why should I hang?” That the superintendent should place this confidence in the negro sweeper appears absurd.

Another damaging point against Conley lies in the declaration of Holloway, timekeeper of the factory, that the negro had appeared for duty intoxicated on several occasions; that his duties as sweeper brought him in contact with the girls, who feared him.

Where Was Conley?

According to Conley’s story, he was on Peters Street from 19 o’clock until 2 in the afternoon of the murder. Police investigation of this has failed to prove the statement. Conley admits that he can not remember anyone whom he saw during that time to bear up his statement. From 2 o’clock until 6 Conley was at his home. This has been proven. Conley declares that from 6 until 8 o’ clock that night he was down town; this also has not been established. Conley states he stayed there the remainder of the night.

According to the new theory of Conley’s implication, the negro wrote the notes on Saturday instead of Friday, as he claims, and not on anybody’s dictation. It is further argued that, in order to ingratiate himself with the law, the made his confession when he thought that the case against Frank was clinched—that his story was the product of his own imagination.

Conley’s delay in making this confession until Frank’s indictment seemed likely is another link against him.

His detailed account of the incident of the note writing, in which he even went so far as to attempt a quotation of what Frank said to him, shows premeditation on the negro’s part, it is argued, and further that the story was conceived by Conley while he was in prison. However, the negro’s childish brain was not capable of making it strong enough to withstand rigid investigation.

E. F. Holloway, timekeeper and foreman of the National Pencil factory, seen to-day by a Georgian reporter, said he was confident the negro Jim Conley, under arrest as a suspect in the Mary Phagan murder mystery, committed the crime.

Here is what Holloway told the reporter:

“Jim Conley, when he came to work here about one year ago, was a pretty good negro. We had no trouble with him for about two months. Then Jim got drunk. He had been running the elevator and we were afraid to trust him afterward. We then put him to work sweeping in the trimming department. Here Conley was closely associated with the girls. He used to move their chairs when he was sweeping. Conley was the only negro allowed in this department.

“Jim got so bad he used to carry whisky with him in his pocket. Several times he was caught by employees taking a drink. This was not known by the management until after the murder of Mary Phagan?

Drunk in Factory.

“About one week before the crime was committed the forelady of the trimming and finishing department, Miss Eulah May Flowers, went to the top floor of the building to look over the stock of boxes. When Conley was not sweeping he was supposed to fill the box bins with boxes. When Miss Flowers moved toward the bin to look in she stumbled over a form. She screamed and fell back. It was Conley. He was dead drunk. Miss Flowers tried to wake him up, but was unable.

Caught Washing Shirt.

“On the morning of the Coroner’s investigation, Thursday after the murder, when the plant was shut down because we all were called to the investigation, I testified and went back to the factory. As I entered the metal department I heard a splashing in the cooling tank. There was Conley washing his shirt. When I entered he was very much startled and tried to hide the shirt by trying to drop it through a crack in the floor. It was a blue shirt and I saw no bloodstains, for he had evidently been washing it for some time as it was pretty clean.

“This is the first time in the year that Jim Conley worked here that he ever washed his clothes here.

“Now, I don’t say Conley was degenerate enough to commit a crime so terrible when he was sober, but I am thoroughly convinced that he strangled Mary Phagan when about half drunk.

“I’ll go further and say that the last three months that Conley was here I was suspicious of him and tried to watch him as closely as possible for I placed no dependence in him. He became indifferent about his work and shiftless.”

Mrs. White Denies Identification.

Mrs. J. Arthur White, of 59 Bonnie Brae Avenue, made positive denial to the Solicitor General’s office Tuesday that she ever had made any identification of James Conley, the negro sweeper at the National Pencil Factory, as published in an afternoon paper.

“I can not understand why such a story should have been manufactured and published,” she said to reporter. “I was just called by the Solicitor General to confirm it, and told him, as I had told him before, that I never had identified the negro.

“I saw a negro sitting on a box on the first floor of the factory as I left there about 1 o’clock in the afternoon of the murder. I did not get a good look at his face. I got just a general impression of his clothes and of his size.

“At the police station ten negroes were brought before me. I picked out one with a green derby and said that he looked considerably like the man I had seen. They told me to look again, and I picked out another man that I thought looked a little more like the negro I had seen, but I never made any positive identification; and I told the detectives, in the first place, that I would not be able to. They never told me the names of the men I had picked out, so I don’t know whether one of them was Conley or not.”

The detectives never have placed much weight on the identification of Mrs. White, as she said that she could not be positive. Added to this is the fact that she saw a negro loitering around the factory at 1 o’clock, which, it is thought, he would have been very unlikely to do had he had anything to do with the disappearance of Mary Phagan, who was in the factory a few minutes after 12 o’clock.