State Charges Premeditated Crime

Atlanta Georgian

August 12th, 1913

Defense Forces Dalton to Admit Jail Record

GIRL DENIES STATE’S VERSION OF FRANK’S WORK ON FATAL DAY

Here are the important developments Tuesday in the trial of Leo M. Frank, charged with the murder of Mary Phagan:

State announces its theory that Frank planned a criminal attack upon Mary Phagan the day before she came to the factory for her money.

The court and chaingang record of C. B. Dalton, the State’s witness who testified that he had seen women in Frank’s office, was shown up by the defense and admitted by Dalton.

Four acquaintances of Dalton testify that they would not believe him under oath and that his reputation for truth and veracity is bad.

C. E. Pollard, expert accountant, testifies that it required him three hours and eleven minutes to compile the financial sheet that the defense claims Frank prepared the afternoon of the murder.

Miss Hattie Hall, stenographer, says that Frank did not work on the financial sheet Saturday morning, the day of the crime.

Jim Conley’s declaration that Lemmie Quinn came into the factory and left before the arrival of Monteen Stover, who came at 12:05 o’clock, is challenged by the testimony of Miss Hall, who swears Quinn did not enter the factory before she left at 12:02 o’clock.

State Announces Theory.

The State definitely announced Tuesday its theory that Frank deliberately premeditated and planned a criminal attack upon Mary Phagan Friday, April 25, the day before she came to the factory and was slain.

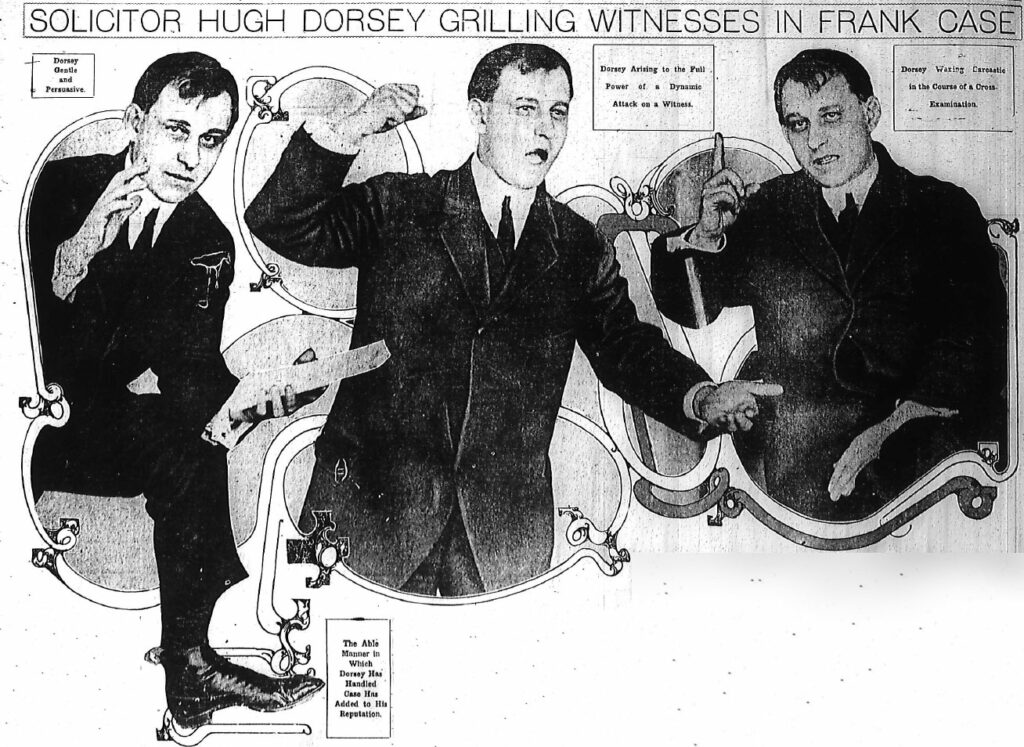

Frank A. Hooper, associated with Solicitor Dorsey in the prosecution, made the surprising announcement of the State’s attitude during a heated argument over the admissibility of a portion of the testimony of one of the defense’s witnesses, Miss Hattie Hall, stenographer at Montag Bros. and occasionally employed at the National Pencil Factory.

Dorsey and Hooper were objecting strenuously to the admission of a phone conversation between Frank and Miss Hall in which Frank was reported to have asked Miss Hall to come over to the pencil factory to assist in the clerical work, saying: “I’ve got so much work to do that it will take me until 6 o’clock to get it done.”

Hooper, after the Solicitor had objected to the question on the ground that it was self-serving and proved nothing, declared that the conservation not only was self-serving, but was made in deliberate anticipation of Mary Phagan’s visit to the factory in the afternoon.

“This remark was made on Saturday morning, the day after Mary Phagan’s pay envelope was refused Helen Ferguson,” said Mr. Hooper. “It was made in anticipation of her visit in the afternoon. It is the State’s contention that Frank deliberately pre-arranged circumstances favorable to an attack upon the girl and incidents serving to divert any suspicion from himself.”

That the State was working upon the theory of premeditation was hinted by the questioning of Helen Ferguson several days ago, but Attorney Hooper’s address to the court was the first open declaration.

The court and chaingang record of C. B. Dalton, a State’s witness against Frank, was given an airing by Attorney Arnold. Dalton was recalled to the stand and made to admit that he had been sent to the chaingang in 1894 on three separate counts for stealing in Walton County.

Dalton also admitted that he had been indicted in 1899 in Walton County for theft and had paid a fine of $141.46.

Attorney Arnold showed the witness copies of four indictments and asked if he knew these had been issued against him in Walton County for selling liquor to Don Tillman and Bob Harris. Dalton denied all knowledge of the indictments.

Witnesses Assail Dalton’s Character.

As soon as Dalton left the stand V. S. Cooper, J. H. Patrick, W. T. Mitchell and L. M. Patrick, all residents of Walton County, were called to the stand and testified that they knew Dalton and that they wouldn’t believe him on oath in a court of justice.

Misses Laura Atkinson and Minnie Smith were called and denied Walton’s [sic] testimony in regard to being in their company.

Dalton testified, when he was called by the State last week, that he had visited the factory basement with Miss Daisy Hopkins and that he frequently had seen Frank in his office with women.

An unassailable alibi was the object in view when the attorneys for Frank began the questioning of a long line of witnesses who were called to testify in regard to every known movement of Frank Saturday, April 26, the day that Mary Phagan was slain.

The testimony of Miss Hattie Hall was the first along this line. That of Alonzo Mann, office boy, was next.

That Frank did not do any work on the financial sheet Saturday forenoon was one of the most important declarations made by Miss Hall. She had testified at the Coroner’s inquest that she assisted Frank in compiling this sheet, but she explained to Solicitor Dorsey that she was mistaken, and it was only one of the tabulations from which the financial sheet was being made that she had worked on.

Her testimony on this point strikes at the State’s theory that Frank did the work in the forenoon.

Miss Hall also testified that Frank signified his desire to have her work […]

Frank Planned Attack, State Alleges

[…] for him at the factory in the afternoon and had asked Harry Gothelmer to come back to the factory in the afternoon, requests which the defense will claim establish conclusively that Frank was not arranging for the commission of any crime or wrongdoing Saturday afternoon.

The witness said that she left the factory first at 12 o’clock as the whistles were blowing, but that she forgot her umbrella and returned to Frank’s office for it, noting that it was 12:02 as she left finally. She declared that she did not see Lemmie Quinn enter Frank’s office. Conley testified that he saw Quinn enter the factory before the arrival of Monteen Stover or Mary Phagan. The Stover girl said she reached the office floor at 12:05 o’clock.

Miss Hall indignantly denied the imputation of Solicitor Dorsey that her salary had been raised as the result of the testimony she was giving. She said that it had been agreed when she entered the employ of Montag Bros. that she was to get an increase of salary August 1, and that she had been unable to get it before this time.

Wade Campbell, an inspector at the factory, came in for a rigorous grilling at the hands of Solicitor Dorsey. Campbell testified that his sister, Mrs. Arthur White, had told him she had seen a negro at the foot of the stairs on the first floor when she went into the factory at 12:30 o’clock.

Campbell Grilled On Affidavit.

“Don’t you know that what she actually said was that she saw the negro at 12:50 when she left?” inquired the Solicitor.

Campbell denied that this was so. The Solicitor then showed Campbell an affidavit and asked if it was not his signature at the bottom. Campbell said that it looked like his writing, but that he would not say positively. He denied that he had made the statement in the affidavit in which he was quoted as saying his sister had told of seeing the negro as she left the factory.

The witness on his redirect examination testified that he had seen Conley reading in the factory several times after the crime. Conley said on the stand that he was unable to read, except for a few simple words.

C. E. Pollard, an expert accountant, was the first witness called. He began to testify as to the time required to make out the finance sheet. Attorney Rosser said that the defense probably would conclude its expert testimony with Mr. Pollard, and that Miss Hattie Hall, stenographer for Montag Brothers, would be the next witness.

Pollard testified that the minimum time in which Frank could have completed the finance sheet was three hours and eleven minutes. This bore out the testimony of Herbert Schiff, Frank’s co-worker, and Joel Hunter, expert accountant.

Over Three Hours To Compile Report.

Q. What is your business?—A. Certified public accountant.

Q. Have you had occasion to go over the financial sheet of the National Pencil Company of the week of April 21 prepared by Leo M. Frank?—A. I went over a copy of it.

Q. Have you also seen the factory record called the pencil sheet?—A. Yes.

Q. Were you also furnished data necessary to make that sheet?—A. Yes.

Q. I will get you to state as an expert how long it would take to complete it?—A. I took each sheet, compiled it, and timed myself as to the length of time necessary. I prepared the sheet of the 24th day. It took me ten minutes.

Q. Were there any mistakes?—A. Yes, a little one—of one and one-half gross. It was hard to say whether it was my mistake or his.

Q. Now state the total time it took you?—A. A total of 191 minutes, or 3 hours and 11 minutes.

Q. Was that the quickest?—A. Yes.

Q. In other words, you took exactly the work that he did?—A. Yes; what I was told he did.

Q. That was steady work without interruption, wasn’t it?—A. Yes.

Q. How long have you been an auditor?—A. Sixteen years.

Q. Have you an office here?—A. I am with the American Audit Company.

Q. That mistake occurred before you took up the sheet, did it not?—A. One mistake was made the Saturday before and one on Friday.

Q. Are those two trifling mistakes—a mistake of 50 cents and a gross and a half of pencils — the only mistakes you found?—A. Yes.

Attorney Hooper took the witness on cross-examination.

Q. Mr. Pollard, this is rather an unusual assignment for you, is it not, to go over a man’s business and undertake to state how long it takes him to do it?—A. No, I think not. Frequently we are called on to estimate the time it takes to do work in changing systems.

Q. Is it not true that a man can work his own books better than anyone else’s books?—A. Yes.

Mr. Arnold took the witness.

Q. How many times would a man have to multiply, divide and subtract in making up that sheet?—A. Well, 40 multiplications and 160 additions, and I can’t guess on the rest.

The witness was excused and Miss Hattie Hall was called. She was questioned by Attorney Arnold.

Q. What is your business?—A. Stenographer-bookkeeper at Montag Brothers.

Q. Do you ever go to the National Pencil Company?—A. When necessary.

Q. On Saturday, April 26, did you see Leo M. Frank?—A. About 10 o’clock at Montag Brothers.

Q. Did he say anything?—A. Yes, he asked me if I could come over and do some work. I told him I didn’t know, but thought I could.

Dorsey interrupted:

“I object to anything he said to her.”

Arnold: “Your honor, it is part of res gestis in this case.”

Dorsey: “Here is this dead girl. They would not let her show what she said at 12 o’clock and I can conceive of no principle of law that would let them show what this man said and not let her show what the deceased said.”

Aimed to Show Conduct.

Arnold: “This is merely to show a course of conduct.”

Judge Roan: “I can see no analogy between the two cases. I rather think you can ask the question.”

Dorsey: “Well, this is a very important point, your honor, and we would like to give you some authorities.”

Judge Roan: “All right.”

Dorsey then read at length from the Eighty-fourth Georgia Report.

Judge Roan: “Do you expect to follow that question by showing that he had certain work to do and engaged her to do it?”

Arnold: “Yes.”

Judge Roan: “Then I will let you ask it.”

Dorsey threw his book on the table and sat down, laughing. Arnold continued the questioning.

Q. When did you call him first?—A. He called me up before 10 o’clock and said he had work enough to do to keep him busy until 6 o’clock.

Dorsey: “Is your honor going to let that telephone conversation in?”

The Solicitor’s objection was overruled.

Q. Miss Hall, did you recognize his voice?—A. I certainly did.

Q. What time did you see him that Saturday morning?—A. About 10 o’clock.

Q. Had you worked for him before?—A. I had been accustomed to going over and helping him on Saturdays. I asked him if he was going to need me. He said, “Yes,” that he had so much work to do that he would be busy until 6 o’clock.

Dorsey Calls Halt; Roan Sustains Him.

Dorsey interrupted, “Your honor, are you going to let that in?”

Judge Roan: “I don’t think I will.”

Arnold: “Your honor, I wish you would let me argue for a moment. Even the State does not claim any crime was committed at that time. There is no reason in the world to suppose that the accused would not have told the truth at that time. I believe that if a part of the conversation is admissible, all of it is admissible. You must admit it all to explain part. You would do this young man an injustice to shut out this evidence of this day’s program, when there was not the slightest motive to be otherwise truthful.”

“Mr. Dorsey has sought to show,” continued Mr. Arnold, “that his financial sheet could have been made up in the morning. We are just trying to show that it was impossible. Now I will read you a decision in which I participated with the father of my good friend, the late Judge Dorsey. It was 24 years ago.”

Rosser: “Are you that old, Mr. Arnold?”

Arnold: “Yes, I am 24.”

Dorsey: “That case has nothing to do with this one. That was a case where a man on trial for murder swore to a lie.”

Arnold: “It was charged that it was a lie. We never did believe it.”

Dorsey: “He was convicted.”

Arnold: “Yes, he was convicted.”

Judge Roan ruled: “Mr. Arnold, this young woman can show that she was called, what she was requested to do and what was shown her to be done. She can state how long she thinks it would take to finish that work. She can not state, however, what he told her over the telephone about what he expected to do.”

Frank Leaves Court With Sheriff.

Arnold: “We want to note an exception to that.”

Q. Miss Hall, what time did you go to Mr. Frank’s office?—A. Between 10:30 and 11 o’clock.

Q. Did you take dictation in his inner office, or in his outer office?—A. In the inner office.

Q. Where did you write it?—A. In the outer office.

At this point Leo Frank went out of the courtroom with Sheriff Mangum. Mr. Hooper jumped up and whispered to Mr. Arnold.

Arnold—Yes, I waived his presence.

Judge Roan—I excused the prisoner properly.

Hooper—I just wanted to know if the defense had waived his presence.

Q. Now, we only have ten orders here. See if they are the ones Frank handed you?—A. Yes. My initials are on them. They are the ones.

Q. Now, the orders are sometimes acknowledged as the first step?—A. Yes; in that case they were.

Q. Do you recall to whom Frank was talking that morning?—A. Yes, but I don’t recall the names. A man and his son came in. Then there was Miss Corinthia Hall and Mrs. White.

Q. Do you recall what any of them said?—Yes; Mrs. White said she wanted to see her husband.

Q. During this time was Mr. Frank working on this financial sheet or any other similar document?—A. He was not.

Q. Are you familiar with his handwriting?—A. Not very.

Q. I will get you to look on this order book and see if those orders are entered.

The wintess [sic] read the eleven orders from the order book.

Q. Now, is that your handwriting?—A. No; I think it is Mr. Frank’s.

Q. Did you write any of these requisitions?—A. No.

Q. Do you know who did?—A. I understood Mr. Frank did.

Q. Were the requisitions made before or after the orders were put on the book?—A. After.

Left Factory At 12:02 P. M.

Q. Now look at these letters and see whether Frank dictated them?—A. Yes.

Q. How many?—A. Eight, and one he did not dictate.

Q. Did he sign them?—A. Yes, I took them to him after I had typed them.

Q. Did he do any work on that financial sheet while you were there?—A. No.

Q. What time did you leave?—A. Just as I got on my hat and started for the door I heard the whistle blow for noon.

Q. Is there a regular whistle that blows for 12 o’clock?—A. Yes, there are several whistles.

Q. What did you do then?—A. I got to the bottom of the steps and remembered that I had forgotten my umbrella. I went back and got it. It was two minutes past 12 o’clock as I passed the time clock.

Q. Did you see any little girl in the building?—A. I did not.

Dorsey took the witness on cross-examination.

Q. Did you call Frank or Frank call you that Saturday morning?—A. I called him.

Q. He had a regular stenographer, didn’t he?—A. They had a stenographer, but she didn’t do but about one-third enough work, so I had to go.

Q. Miss Hall, what were you receiving at that time?—A. Ten dollars and fifty cents a week.

Q. What are you getting now?—A. Fifteen dollars a week, and I want to explain——

Q. Never mind, just answer my questions. Didn’t you state in a soda fountain last night that the raise came to you without asking for it after it was known that you were to be a witness?—A. Indeed, I did not. I don’t go to soda fountains. I want to explain?

Attorney Arnold—Let her explain.

A. I insisted that they give me this raise on July 1, but they couldn’t give it to me until August 1.

Q. Did Frank come to Montag’s before or after he called you up?—A. After.

Q. You are the one who called him up?—A. Yes.

Q. You did the insisting about going to his office?—A. I certainly did not.

Q. Did you not swear at the Coroner’s Inquest that Frank left Montag’s before you did?—A. I said I did not recall.

Q. You acknowledged these orders with a postcard and letter?—A. Yes.

Q. You wrote those between 10:30 and 12?—A. Yes.

Q. Did you state to the jury Frank left before you did?—A. I don’t recall.

Q. How long would it take you to fill out the blank?—A. I never timed myself.

Talked Over Time With Office Boy

Q. Didn’t you swear before the Coroner that it would not take more than one minute?—A. I don’t know.

Q. Did you say Frank was at the office when you got there?—A. I said I did not recall.

Q. Who came in while you were there?—A. Two men and three women.

Q. What time was it the office boy left?—A. 11:30.

Q. Didn’t you tell the Coroner you could not tell the time?—A. Yes.

Q. How do you know now?—A. The boy told me.

Q. You talked it over with him?—A. Yes.

Q. Where were you when those people came in?—A. In the outer office.

Q. How long were you there when these came in?—A. I do not recall.

Q. Didn’t you tell the Coroner it […]

RESIDENTS OF DALTON’S HOME COUNTY RIDDLE HIS CHARACTER ON STAND

[…] was fifteen minutes?—A. I don’t remember.

Q. How long was it after those letters were dictated that you commenced writing?—A. Two minutes.

Q. Can you tell how long you were writing those letters?—A. No.

Q. When you were writing those letters, where was Frank?—A. In his office.

Q. After you finished, what did he do?—A. I took them in to him.

Q. Did he say anything?—A. He said he would put them in the envelopes and mail them.

Q. He said you need not wait?—A. Yes.

Q. Did you get anything there Monday?—A. I got the timebook and some papers.

Q. The previous Saturdays when you were over there, do you remember Frank working on the financial sheet that morning?—A. No; I helped him get up something about gross—I found afterward it was the average sheet.

made it up. I helped him by transferring some of the things to the sheet?—A. Yes, but I thought it was the financial sheet.

Q. Didn’t you state at the coroner’s inquest that you helped him the Saturday before?—A. Yes.

Found Her Error Herself, She Says.

Q. When was it you discovered it was not the financial sheet?—A. I don’t know, but I want you to know I discovered the mistake myself.

Q. Now, were you not at the factory the previous Saturday and helped him?—A. Yes.

Q. Did you not have that financial sheet before you at the Coroner’s inquest, and did you not identify it?—A. I don’t think so.

Q. Well, you said he was working on the financial sheet that previous morning?—A. He was not.

Q. Did you not tell the Coroner’s jury that you were in the outer office the entire time?—A. I don’t know.

Q. Now explain how your mind underwent this change. You said then you were not in his office and now you say you were.—A. I was rattled before the Coroner, because I had never been in a courtroom before.

Q. Now, didn’t you say in response to the question, “Do you know what a financial sheet is?” that you did?—A. But I was thinking of the average sheet.

Q. Now, what did you mean by telling the Coroner some of those girls came in for their pay and now saying the only one you know anything about came in for her coat?—A. I just forgot.

Q. Now, didn’t Frank say that morning that he would not get up that sheet until Herbert Schiff came down and got up the necessary data?—A. Yes, he said he could not go on with his work until Schiff came down.

Q. You do know that Frank said positively he could not make up that sheet until Schiff had gotten up certain data?—A. He did not positively say so. He said he did not mind Mr. Schiff being off if he had done his work, but that he had not done his work.

Q. Miss Hall, didn’t you swear before the Coroner’s jury that you worked on this financial sheet which is written in ink the Saturday previous, and now to-day you swear it was this sheet, which is written in pencil?—A. I did not. I was identifying the handwriting on that sheet.

Q. You said lots of people wrote slanting, and it was hard to identify?—A. Yes.

Q. While you were working in Frank’s outer office, you said he was very quiet and you did not know what he was doing?—A. Yes.

Q. You do not know whether he was working on the financial sheet or not?—A. Yes; I saw the papers on his desk that he was working on, and the financial sheet was not among them.

Attorney Arnold took the witness.

Q. Why did you tell Mr. Frank you had to get away at 12 o’clock?—A. He said something about wanting me to help him in the afternoon. I told him I had to get away at 12 o’clock, and I did get away at 12 o’clock.

Dalton’s Prison Record Exposed.

Dorsey objected to the answer, but was overruled.

Miss Hall was excused and C. B. Dalton was recalled to the stand.

Arnold questioned him.

Q. Who is Andrew Dalton?—A. A brother-in-law.

Q. With the same name?—A. Yes.

Q. Who is John Dalton?—A. He is my brother.

Q. Weren’t you three sent to the chaingang at the special term of the Walton County Superior Court in 1894?—A. No.

Q. You were not?—A. I was, but the others paid out.

Q. What did you steal?—A. A chop hammer.

Q. Didn’t you plead guilty to two more charges?—A. That is the only time I ever went to the chaingang. I don’t know how long I served, but I was pardoned in March.

Attorney Arnold moved that the witness’ reply in reference to being pardoned be struck from the records.

Q. Didn’t you plead guilty to three charges all at the same time? And that the sentence was concurrent on the three charges?—A. All I took was a chop hammer. One of the other boys took a plow stock.

Q. At the February term of 1899, were you not indicted for stealing a bale of cotton?—A. For helping.

Q. Were you found guilty?—A. I was fined $146, which I was paid.

Q. After that, did you not go into Gwinnett County and steal?—A. I was indicted for stealing some corn, but I was found not guilty.

Dorsey took the witness.

Q. How long since you were in trouble?—A. Eighteen years.

Dorsey to Recall Daisy Hopkins.

Arnold took the witness.

Q. Is it not a fact that there are now four indictments against you in Walton County for selling liquor?—A. If there are I don’t know it.

Q. Is it not a fact that they let you get out of the county and were glad to get rid of you?—A. I have been back there every year.

Dorsey took the witness.

Q. Do you know that Daisy Hopkins knows Leo Frank?—A. I do.

Q. How do you know?—A. She told me she knew him, and then I saw her talking to him.

Arnold interrupted: “I object to what she said?”

“That’s all right; then,” Dorsey replied, “I will recall her.”

Dalton was excused and the defense began an attack on his character with witnesses from Walton County.

B. S. Cooper, the first witness called, was accompanied by a small boy of 6. He held the boy on his lap while he testified on the witness stand. Arnold questioned him.

Q. What is your business?—A. A farmer.

Q. How long have you been in Walton County?—A. Fifty years.

Q. Do you know C. B. Dalton?—A. I do.

Q. Do you know his general character?—A. I do.

Q. Is it good or bad?—A. Bad.

Q. Would you believe him under oath?—A. I would not.

Wouldn’t Believe Him Under Oath.

At this point, C. B. Dalton, was called for but could not be found. Dorsey said he would admit that the witness was speaking of the Dalton who had testified against Frank. Hooper was excused and J. H. Patrick was called. Arnold questioned him.

Q. Where do you live?—A. In Walton County.

Q. What do you do?—A. Carpenter and bailiff.

Q. Have you seen Dalton here this morning?—A. I shook hands with him.

Q. Do you know his general character for truth and veracity and is it good or bad?—A. Bad.

Q. Would you believe him on oath?—A. No.

The witness was excused and W. T. Mitchell was called. Arnold questioned him.

Q. Where do you live?—A. Walton County.

Q. Do you know C. B. Dalton?—A. Yes.

Q. Have you seen him this morning?—A. Yes.

Q. Do you know his general character?—A. Yes.

Q. Would you believe him under oath?—A. No.

The witness was excused and I. M. Hamilton was called. Arnold questioned him.

Q. Where do you live?—A. Walton County.

Q. What is your business?—A. Farmer.

Q. Do you know C. B. Dalton?—A. Yes.

Q. Would you believe him under oath?—A. No.

The witness was excused and Miss Laura Atkinson, of No. 30 Ella street, Atlanta, a woman apparently 35 years of age, was called to the stand. Arnold questioned her.

Q. Where do you work?—A. At the Empire Printing Company.

Q. Did you ever work for the National Pencil Company?—A. Yes, for two days.

Denies Dalton’s Story of Strolls.

Q. Do you know C. B. Dalton?—A. Yes.

Q. Did you ever walk home with him from the Busy Bee Cafe on Forsyth street?—A. I did not.

Q. Were you ever with him around the National Pencil Company?—

Dorsey interrupted: “I object,” he said. “The witness said nothing that reflected on this woman.”

Arnold: “It was a reflection for him to say that he was with her.”

The objection was sustained.

Dorsey took the witness.

Q. How long have you known Dalton?—A. About six months.

Q. Were you ever in his company?—A. I have been in his company three times.

The witness was excused, and Mrs. Minnie Smith called. Arnold questioned her.

Q. Where do you work?—A. National Pencil Company.

Q. Are you the Mrs. Smith who lives at No. 148 South Pryor street?—A. Yes.

Q. Are you the only Mrs. Smith at that address?—A. Yes.

Q. Do you know C. B. Dalton?—A. No.

Q. Were you ever in his company?—A. No.

The witness was excused. Alonzo Mann, the office boy at the National Pencil Factory was then called. Arnold questioned him.

Q. Where do you work?—A. At the National Pencil Company as an office boy.

Q. How long have you been there?—A. Since April 1 of this year.

Q. Where do you stay when you are not at work?—A. Right outside the office.

Left Frank and Miss Hall in Office.

Q. How late do you work on Saturdays?—A. I had only been there two Saturdays before the murder.

Q. You don’t know how late you stayed?—A. No.

Q. What time did you leave the office Memorial Day?—A. At 11:30.

Q. Who did you leave there?—A. Miss Hall and Mr. Frank.

Q. Do you recall what you did that morning?—A. No.

Q. Did you phone Mr. Schiff?—A. Yes. Mr. Frank told me to, but I could not get him.

Q. How late did you stay those other Saturdays?—A. 3:30 to 4 o’clock.

Q. Did you see Mr. Frank bring any women there and buy them drinks?—A. No.

Q. Who do you recall seeing there that day?—A. Mr. Holliday, Mr. Irby, Mr. McCrary and Mr. Darley.

Q. Can you recall anybody else?—A. No.

Q. Did you see Corinthia Hall?—A. I don’t remember.

Q. Did you see a man come in to see about his boy?—A. I don’t know.

Dorsey took the witness.

Q. What time did Mr. Frank get there that morning?—A. I don’t remember.

Q. Did he go out?—A. One time, as I recall.

Q. Do you know how long he was gone?—A. No, I can’t remember.

The witness was excused and Wade Campbell was called.

Arnold questioned him.

Q. Where are you employed?—A. I have been at the National Pencil Company for a year and a half.

Q. Do you recall a conversation with Mrs. White the Monday following the murder?—A. Yes.

Q. Can you tell me what she said?—A. She said that as she went into the factory at 12 o’clock she saw a negro sitting there. She said that when she came down he was not there, and she heard voices, but could not tell where.

Q. Were you at the factory Saturday?—A. Yes.

Q. At what time?—A. About 9:35.

Q. Did you see Frank?—A. Yes; I went right to his office.

Q. Did he say anything?—A. Yes; I was jollying him and he was jollying me.

Q. Were you on the fourth floor Tuesday morning?—A. Yes.

Q. Did you see Jim Conley up there?—A. No.

Dorsey took the witness on cross-examination.

Q. Do you board with Mr. Darley?—A. I did.

Q. Where were you Saturday night of the murder?—A. I don’t know.

Q. Didn’t you go to the Bijou that night with Mr. Darley?

“I object,” said Rosser.

Judge Roan sustained the objection.

Q. Darley is a married man with five children, is he not?—A. Yes.

Q. Did you see Miss Dixon that night?

Rosser—I object.

Judge Roan sustained him.

Q. You reported to Darley on April 28 that your sister had seen a negro in the pencil factory on Saturday, about 10 o’clock?—A. Yes; he sent me to see my sister.

Q. What did she tell you?—A. She said she saw a negro man on the first floor. She said she heard some indistinct voices as she went in.

Q. You saw that blood on the second floor?—A. I saw what they said was blood.

Q. How did it look?—A. I didn’t notice it close enough to tell about it.

Grilled Concerning Statement to Dorsey.

Q. Where do you work?—A. As an inspector at the National Pencil Company.

Q. You made a statement on May 12?—A. I made a statement to you. I don’t remember the date.

Q. Didn’t you state that your sister said she saw the negro as she was coming out?—A. I did not.

Q. You deny it then?—A. I do.

Q. Is this your signature?—A. It looks very much like it.

Q. You can’t swear that this is your signature?—A. I would not swear it.

Q. You say that you don’t know whether that is your signature?—A. Yes.

Q. Do you deny making this statement?—A. I told you I did.

Q. Did you not read over this statement and make certain corrections?—A. Yes.

Q. Did you not say in this statement that your sister went there at 12:30 and could not see her husband and went back?—A. I don’t know.

Arnold the witness.

Q. How did you come to go to Dorsey’s office?—A. I received a subpena.

Q. You thought you had to go?—A. Yes.

Q. Didn’t you know that it was not worth the paper it was written on?—A. No.

Wanted To See Corrections Made.

Q. Did you just point out these corrections or did you wait and see that they were made?—A. I think I waited.

Q. Who was there?—A. Starnes, Campbell and Dorsey.

Q. Did they all ask you questions?—A. Yes.

Q. All of these 21 pages are your statement?—A. Yes.

Q. You were asked all of these questions?—A. Yes.

Q. Were you naked at the time you were in the office if anyone came in and did you answer “No”?—A. Yes.

Q. You answered that someone came in to get their pay?—A. Yes.

Q. Do you know this negro Jim Conley?—A. Yes.

Q. After this murder do you recall seeing him reading newspapers?—A. Yes.

Q. Where?—A. On the fourth floor.

Q. How many times?—A. Twice.

Q. Is it anything unusual to see spots on the metal room floor?—A. No.

Q. Have you seen the place where Conley said he found the body?—A. No.

Dorsey took the witness.

Q. Where was Conley sitting when he was reading the paper?—A. By the elevator.

Q. Where was he the second time?—A. In the rear of the building.

Q. What paper was he reading?—A. I don’t know.

Q. Do you know whether he was reading about the crime?—A. No.

Q. Was it an extra?—A. I think so.

Q. You knew Conley could write?—A. Yes.

Q. You did not report it to the officers?—A. No.

Q. Did Frank know he could write?—A. I don’t know.

Q. Where did you see him writing?—A. In the boxroom.

Q. Did you ever see him writing with a pencil?—A. Yes.

Q. Who did you tell what your sister told you?—A. Mr. Darley.

Q. How often did you see those spots in the metal room?—A. Occasionally.

Q. How often have you seen those spots in the hall?—A. Oh, very often.

Q. Did you see the spots where those chips were taken up?—A. Yes.

Q. You saw those spots everywhere, what everybody said was blood, and yet you tell the jury you didn’t pay any attention to it?—A. Yes.

Q. Other people got down and looked at them, didn’t they?—A. Yes.

Rosser interrupted.

“I object to what other people said and saw. It is utterly immaterial and irrelevant,” he said.

“We want to show,” said Mr. Hooper, interrupting, “that this man was interested and that he went out to see his sister about the negro, and yet he came back there and was in no way interested.”

“I think you can ask questions along that line,” said the court.

“Well, we want to record an objection,” said Rosser.

Q. Where and when have you ever seen on that second floor anything that looked like that spot?—A. I did not look close enough at it to know.

Q. When did you see other spots like it on the floor of the metal room?—A. There were other spots, but I don’t know whether they were like that spot or not.

Q. Did you talk to your brother-in-law about what your sister said?—A. He told me about it.

Court adjourned until 2 o’clock.