Grief-Stricken Mother Shows No Vengefulness

August 11th, 1913

Atlanta Georgian

By TARLETON COLLIER.

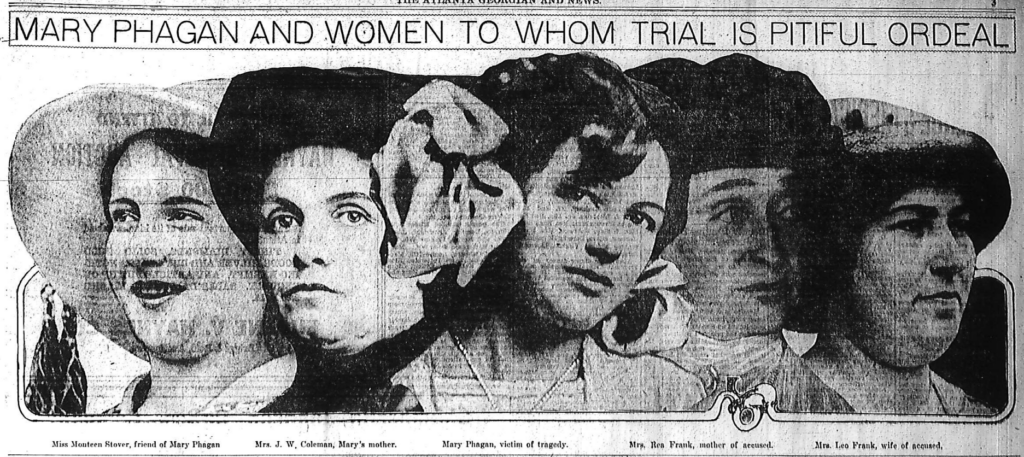

That black-clad woman in the corner of the courtroom—nobody has noticed her much. Things have happened so swiftly in the Frank trial that all eyes are on the rush of events, waiting for a quiver on the face of Leo Frank, watching with morbid gaze the brave faces of Frank’s wife and his mother, studying the passing show that the numerous witnesses present.

And the woman is so unobtrusive, so plainly out of it all. The tears, whose traces are evident on her face, were not shed as a result of this trial. The lines under her eyes are older than two weeks. Her sorrow—and it is plain that she has undergone sorrow—came some time ago. Now, the first poignant pain of it has passed and only a dull ache remains.

All that is plain as she sits in the courtroom in an attitude which bespeaks much of listlessness and resignation. The thoughts that pass in her mind are revealed in that attitude and in her placid face. And the sum of them is this:

No matter what happens, the dull ache will always be there at her heart.

Mary Phagan’s Mother.

Because, you see, it is her little girl that all this is about. The black-clad woman is Mrs. W. J. Coleman, Mary Phagan’s mother, and Mary Phagan is dead.

Mrs. Coleman has not been in the courtroom during all the trial. Much of the time she has been in the room upstairs, kept there because she was a witness. And witnesses must not see nor hear what is going on in the courtroom before they are called, even if the names of their own little girls are handled back and forth.

But now Mrs. Coleman has testified. She has looked upon the bloodstained, pitiful clothing of her daughter, the clothing that was publicly shown, the intimate garments that were upheld before hundreds of eyes. She has announced for purposes of court record that they are Mary’s.

She has explained how she last saw her daughter alive. She has told how Mary Phagan ate her last hurried meal of cabbage and bread and then went out to a horrible death. Now, she may come out of the witness room and listen to all that other persons have to say about Mary, alive and dead.

Now she may sit in a corner of the courtroom and hear that her daughter was beaten and choked and killed.

She may listen, perhaps with a pang of jealousy, to other persons tell that they saw Mary Phagan alive, happy and serene, long after she kissed the little girl good-by for the last time.

It is her Mary that they are talking about, the little girl whom she held in her arms as a baby, whom she watched grown up to be a capable worker, with a spirit unspoiled, with a laugh as free as in the baby days, with a hundred dreams and hopes there on the edge of young womanhood.

Testimony Bewilders.

Mrs. Coleman wears a look of bewilderment at times, as she tries hard to follow the intricacies of the testimony. Sometimes they are not talking about Mary Phagan at all, but about expense accounts and balance sheets and clocks. What has all that to do with her little girl?

It is when the witnesses are talking about these incidental bits in the chain of circumstantial evidence that the black-clad mother is most the listless and passive figure of resignation. It is then that she looks around, with her wide-open stare, as if in wonder that her little girl could be the cause of it all.

But even when the name of Mary Phagan is mentioned, the mother is not noticeably attentive. Her eyes cease their wandering, but her body changes nothing of its posture of listlessness, loses none of its air of being detached from the courtroom and its incidents.

She is there plainly without resentment toward any one in particular. There is no vengefulness in her soul—you can read that in her face. It is almost as if she, having suffered so much, is unwilling that any others suffer. She sits there and looks, curiously, wonderingly, a little dully.

And sometimes they mention Mary Phagan’s last meal of cabbage. It is remarkable that a dish of homely cabbage should become a great thing. There is something grimly ludicrous in the situation. And there are some, the irreverent and the unfeeling, who have made it a subject of jest.

Glorified in Love.

But to Mrs. Coleman there must be something appealingly intimate in the subject. She cooked the cabbage. She chopped it and prepared it as her little daughter liked. The simple meal was glorified by the love that must have gone into its making—housewife love for those in her care, mother-love for the whims and desires of her children. The cabbage subject must be of tremendous interest to Mrs. Coleman.

Whatever her interest, though, it is never keenly shown. Apathy seems to be the chief characteristic of her in the courtroom—no, not apathy, but just a dull wonder.

You read plainly from her worn face and her figure that she is not seeking vengeance. Sometimes you might wonder why she is there in the courtroom. You establish curiosity as the motive, curiosity and natural, jealous, mother-desire to hear directly from the mouths of others something about her little girl as she last was seen.

It must be almost like awaiting a message that she is there, pursing her dull grief.